This exhibition is twofold in nature. It is about two architects – João Gomes da Silva and Paulo David – and two disciplines, and deals with two quite distinct geographies: the island of Madeira and the city of Lisbon. But this exhibition is not about the history of the relationship between the two architects. It starts with their collaborations together, but then it moves from this central core to look at other individual projects, other geographies and other times. It is not an exhibition about a common history, but the illustration of a path that begins with a common core of works and then goes off in other directions. From a more ambitious and comprehensive standpoint, Landscape as Architecture is, above all, designed to provoke reflection about the complex relationship between landscape and architecture.

The projects presented do not follow any chronological principle, but appear here because they develop themes that bring us closer to understanding the possible relationship between architecture and landscape proposed by the work of the two architects. The exhibition does not seek to simplify this relationship, but to emphasise its wide-ranging and problematical nature. The temptation has been avoided of closing off concepts or putting forward disciplinary or programmatic principles, because we know that the theme of landscape is so profound that it would oblige us to examine many other arts besides architecture if we were to do it full justice. Only in that way would it be possible to establish a rigorous framework for the idea of landscape, presenting it in its dimension of something that is built, fabricated and originated by man.

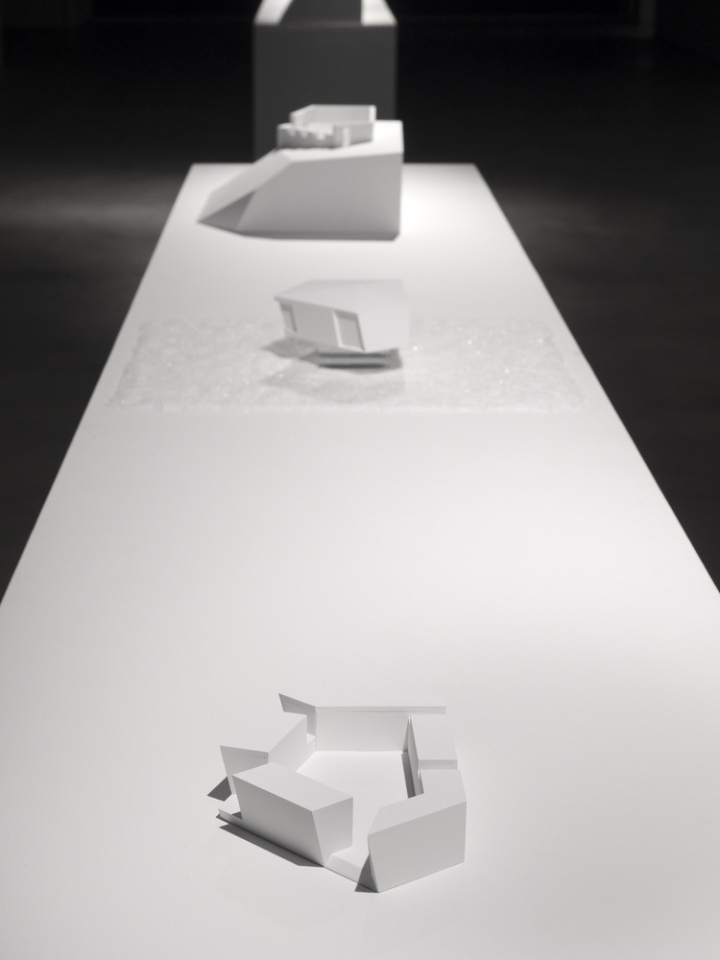

Landscape is the place of a tension or, if you prefer, of a conflict, an old and rather primitive conflict that is still to be found in all human gestures that seek to create form and produce meaning. At a certain level, this conflict is waged between reason and nature and can be understood as a kind of basic and constitutive polarity between form and substance, the logical and the empirical, or even between idea and construction. Nature signifies those frequently paradoxical and confused aspects of reality that withstand the human desire for order and its wish to impose a form upon the world. The modern narrative, believing in progress and in human productive forces, was convinced that the resistance shown by the world’s empirical substance, and with it nature, should be overcome and integrated into a dialectic in which man would always be the dominant and triumphant element. This exhibition places itself at the very centre of these tensions.

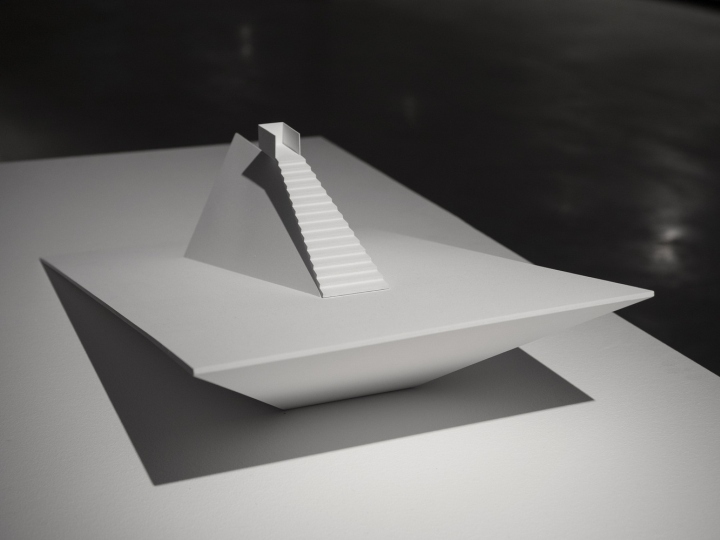

It is not a question of creating a hierarchy or of tracing a path between our different understandings of architectural material structures as monuments, functions or nature, but of examining the possibility that nature itself might be the guide of architecture. A possibility that does not imply forgetting the different rationalities or the different technical and functional requirements that the discipline of architecture involves, nor does it mean proposing the possibility of an architecture that, as Rosario Assunto says in Nature and Reason, mimetically reproduces nature, but instead critically thinking of a way of acting that is not guided by the beauty of pure, geometrical and ideal forms, but which begins and ends in nature.

Nature is not synonymous with “natural” or with biology, but is to be seen as geography, territory, history, culture, etc. And it is this form of nature that the works of João Gomes da Silva and Paulo David call upon, in the sense that their gestures, turned into form and substance in space, are ways of understanding the world, interpreting the territory and thinking about history, architectures that not only seek to impose objects upon the world, but to live in a kind of intrigue between human construction (rational, logical, geometrical) and the spontaneity of nature (irrational, spontaneous and sensual).

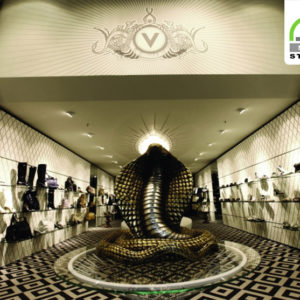

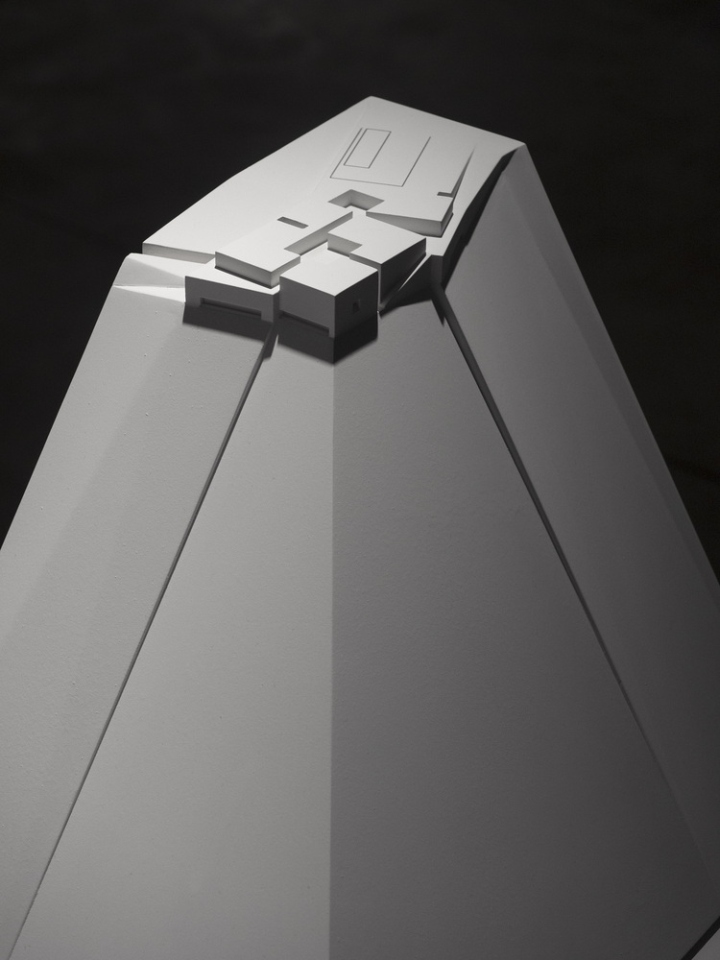

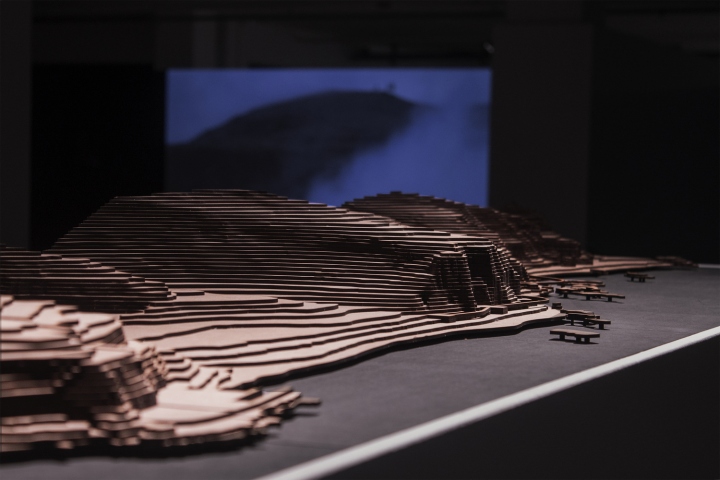

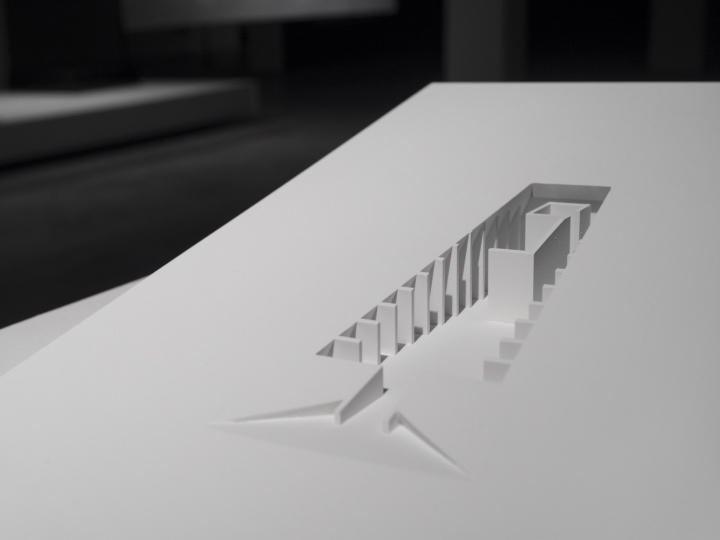

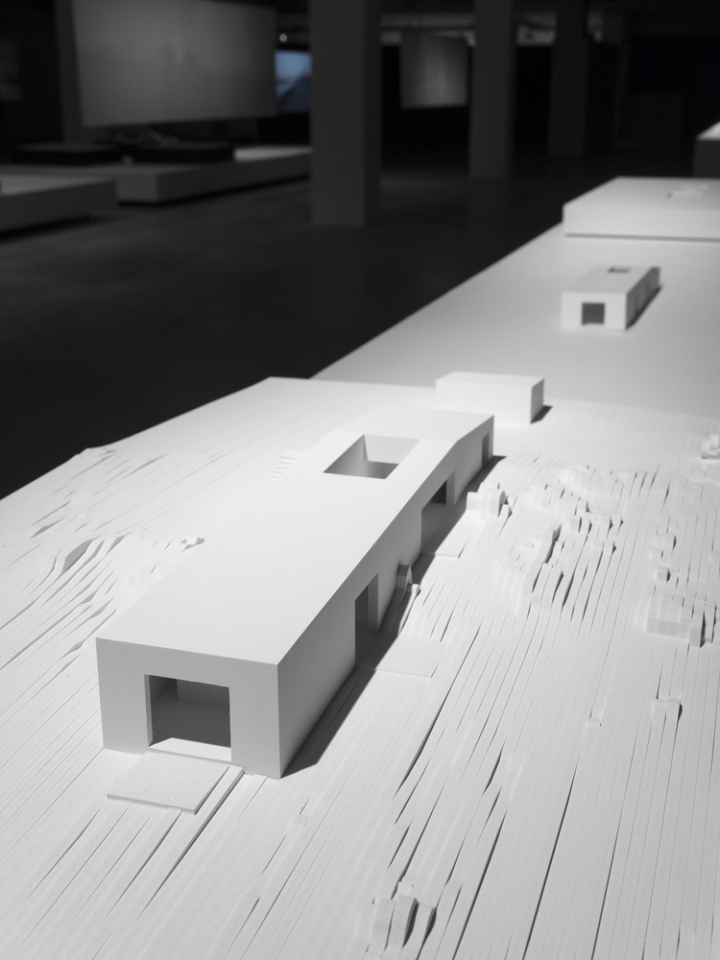

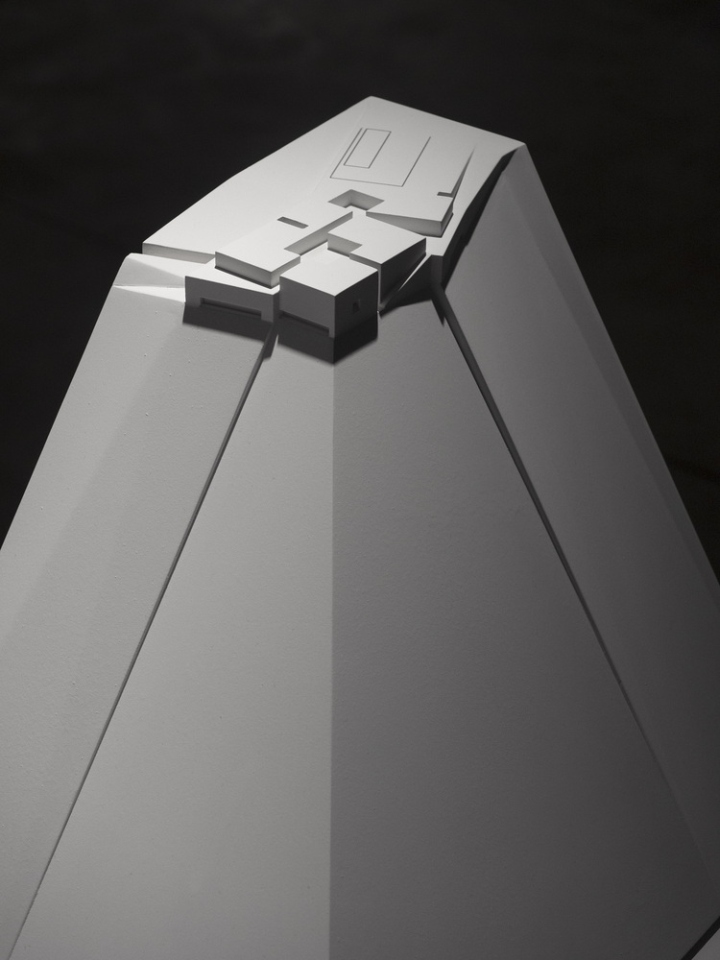

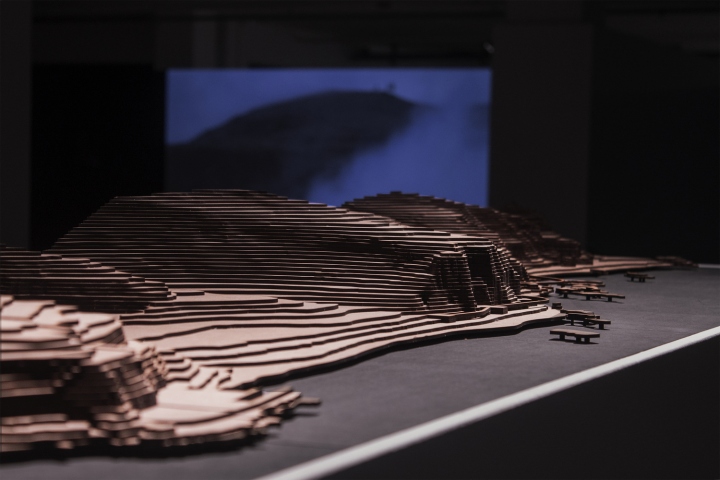

But this exhibition is not confined to the idea of landscape and its questions. It also examines the modalities, materialities and concepts with which a place is constructed, as if, through the collaborations and projects of these two architects, we were attempting to answer the question: how does one construct these kinds of places that seem as though they have always existed? and which, seemingly immune to the passage of time, allow us to guess their beginnings or their genealogy: places without time, which appear to have always been there and where their antiquity is their future. How can we imagine Calheta in Madeira without the Casa das Mudas, where each volume, window and material is an integral part of that coastline? Or how can we think of the Ribeira das Naus in Lisbon as not having always been like this? It is interesting to understand the way in which, in these two projects, a strategy is devised that will reveal what, in a territory, lies hidden in its deepest layers. Seen in this light, architecture appears as a way of critically recovering – activating, making present, operative and pertinent – something that previously existed. It is not a question of choosing the idea of antiquity as the main value, but of viewing architecture from the idea of belonging: architecture that is not based on a desire for formal or technological invention, but on the feeling of belonging, or, in other words, its original questioning is about what belongs to a place. For this reason, as Álvaro Siza Vieira writes, architecture is never entirely free because there is always something – even in the middle of the Sahara Desert – that obliges us to postpone the test of its Great Freedom and head off in another direction: the turban of a nomad, a gold coin or a drawing carved into the wall of a cave.

Although the question of place is not new, it has become pertinent in our present time because we are all subject to the intense feeling of no longer having a place. It is not a form of nostalgia or melancholy, but a question of critically approaching the (strange) idea of a generic place, of the need that we feel, so well expressed by the works of these two architects, to associate the geographical place with history and culture.

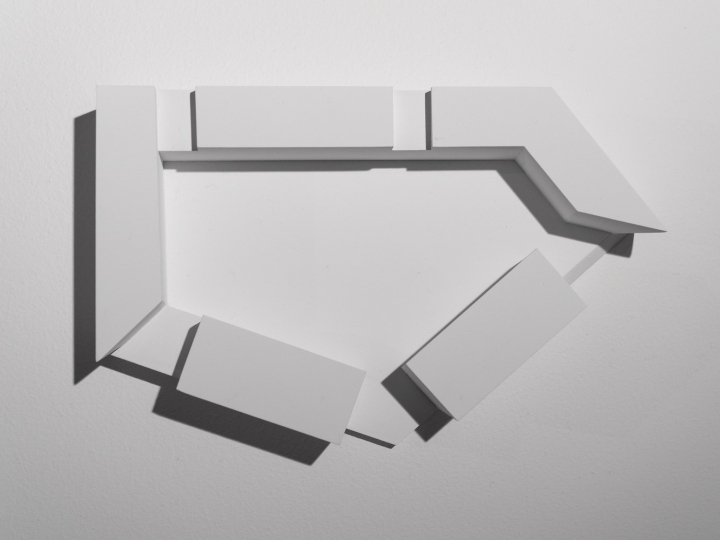

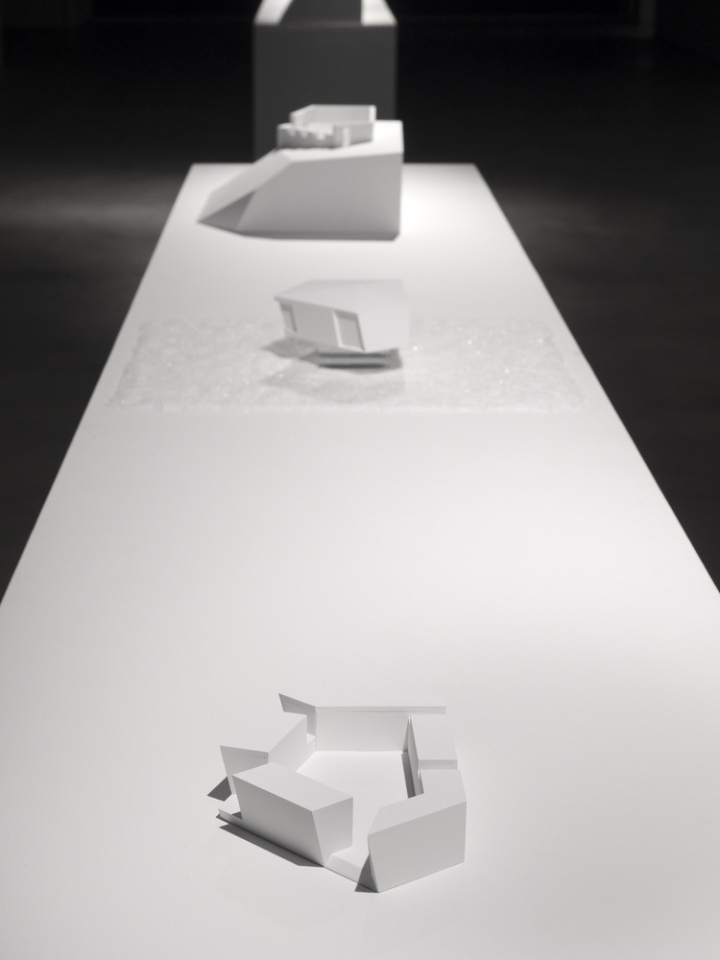

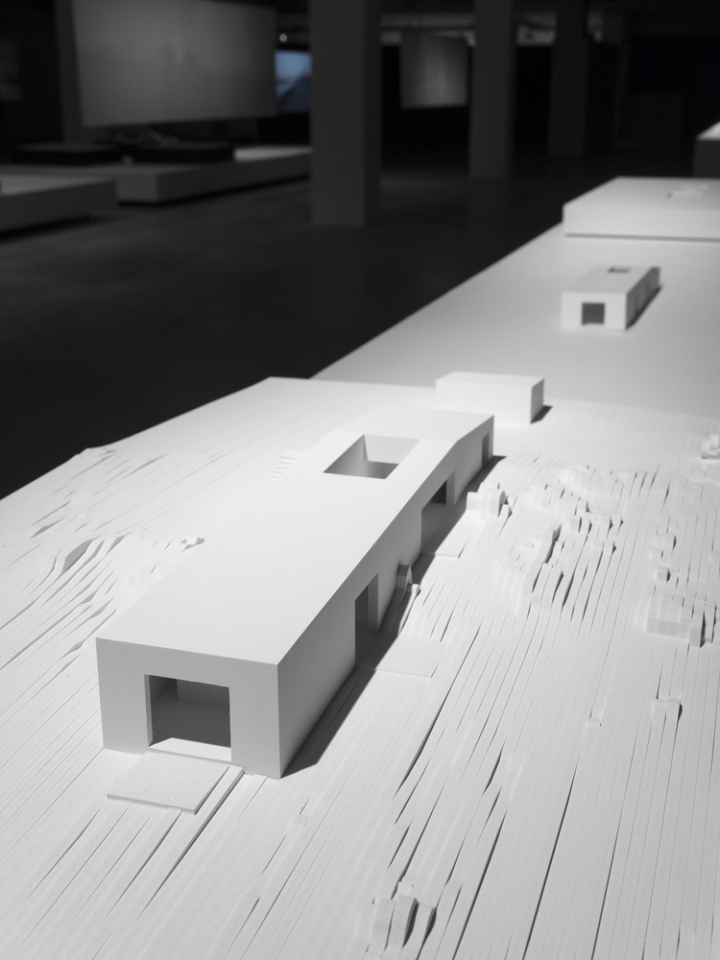

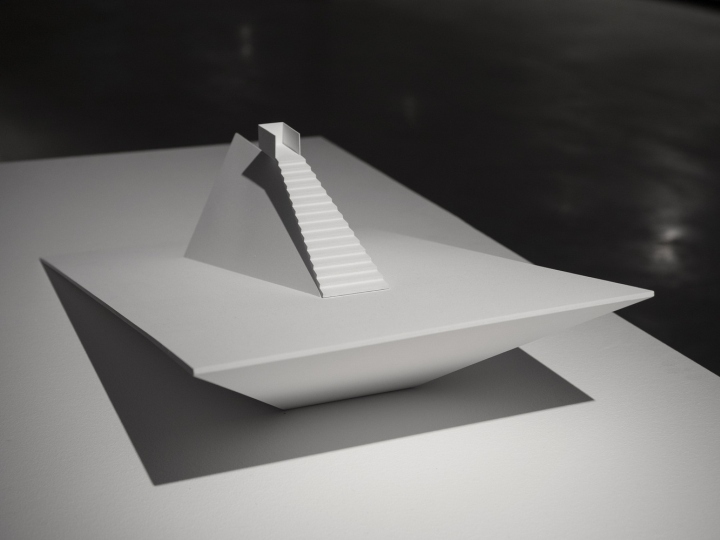

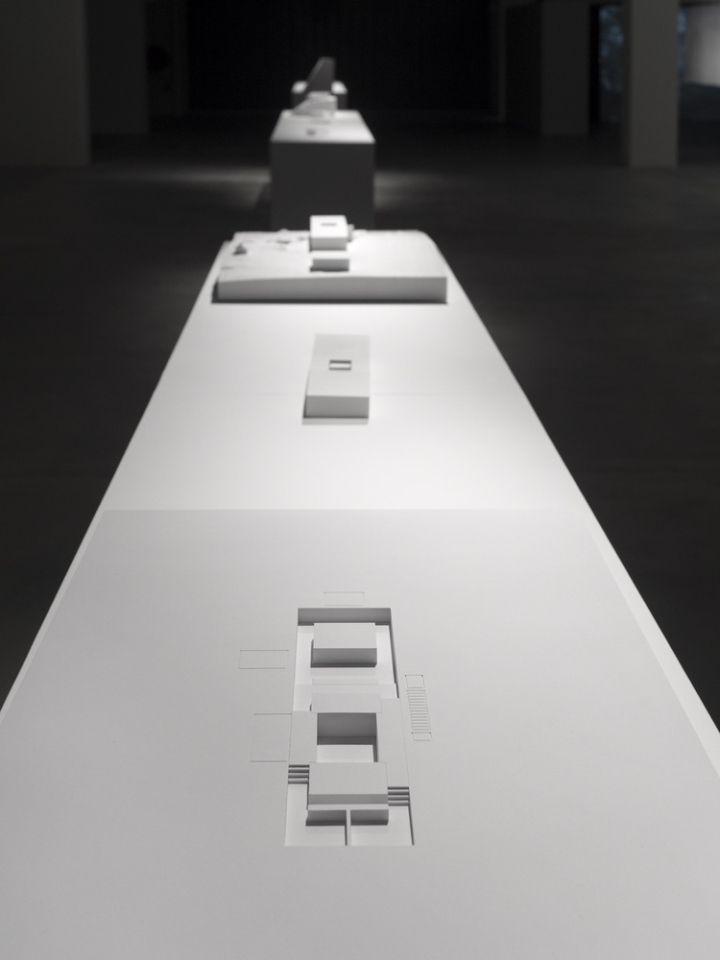

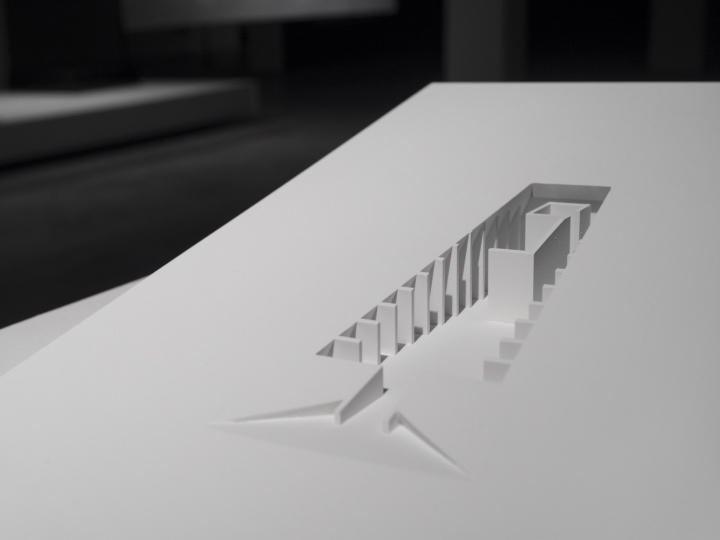

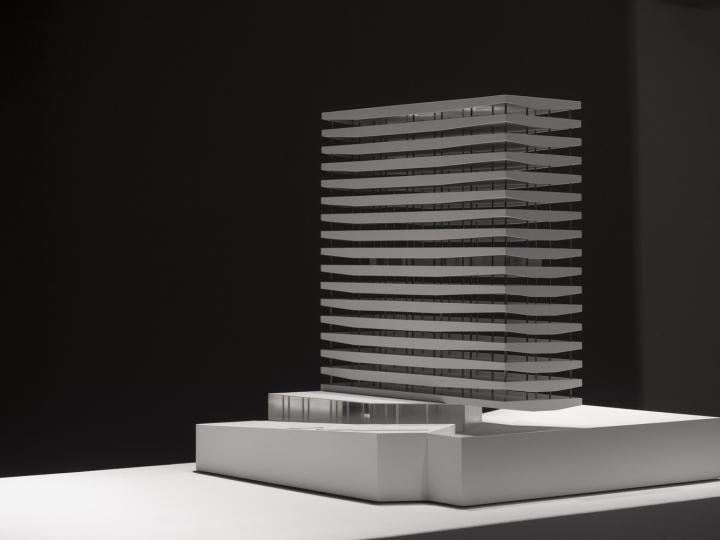

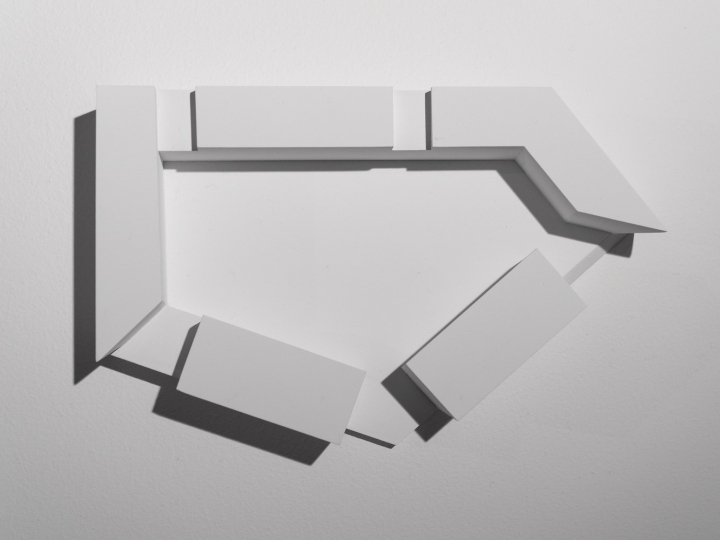

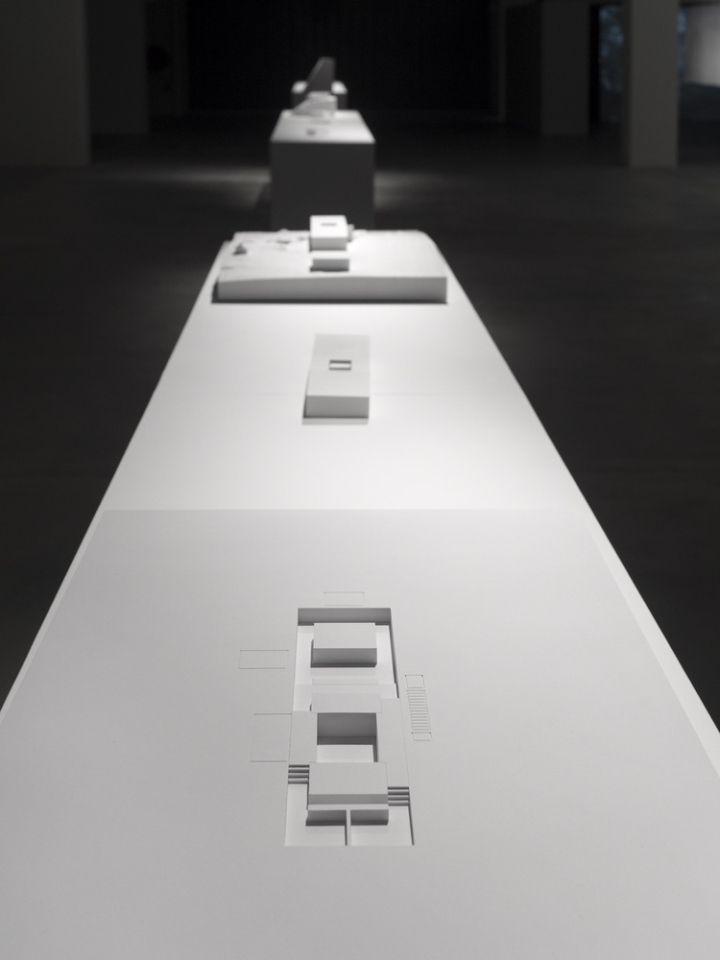

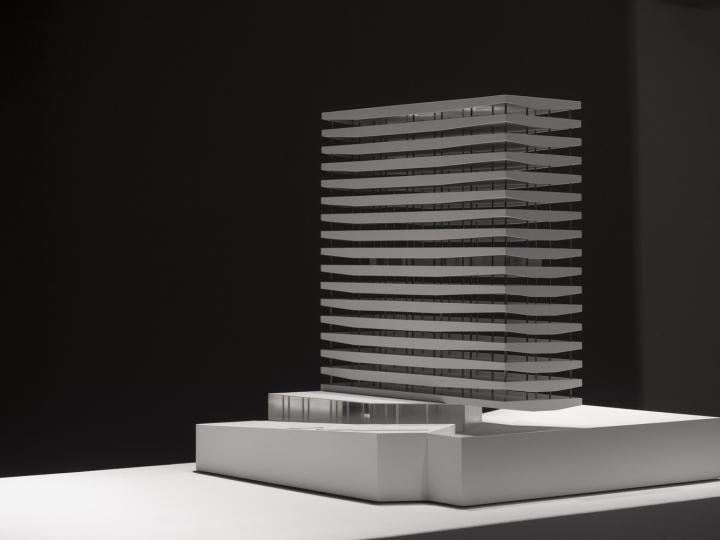

It is also important to stress the way in which the question of the representation of architecture is raised through the confrontation of different ways of representing a space, a place and a geography: material fragments, technical drawings, architects’ models, photographs, drawings, words. A labyrinth of elements where a comparison is made between personal, cultural, historical and disciplinary geographies, which is prolonged in the previously unseen videos and photographs by Nuno Cera. The images (fixed and moving) appear as a kind of notebook in which the different textures and intensities of architecture and landscape take both form and shape. These are not photographs of architecture in the normal sense, but subjective, artistic and poetic approaches to the unity between form, substance, desire and place that makes architecture a landscape.

Architects: João Gomes da Silva and Paulo David

Photography: Fernando Guerra | FG+SG , Diogo Nunes, Stefano Serventi

http://www.archdaily.com/791988/landscape-as-architecture-joao-gomes-da-silva-and-paulo-david

Add to collection