Crystal is one of the most enigmatic forms – at once representative of extraordinary geological forces of unfathomable spatial and temporal dimension, and next a legendary artifice of Venetian glassmakers. Self-replicating, but not alive, in its natural state it is a phenomenon the visual perfection of which is virtually unattainable. It is in these supernatural and phenomenological characteristics of mineral and glass that Japanese designer Tokujin Yoshioka has located a medium of enormous cultural resonance.

A designer who works across product, interior and exhibition design, Yoshioka’s recent shop fitout for Swarovski’s flagship boutique in Ginza, Japan, carves crystal into a spatial envelope that reflects back aspirations of lavish consumer culture.

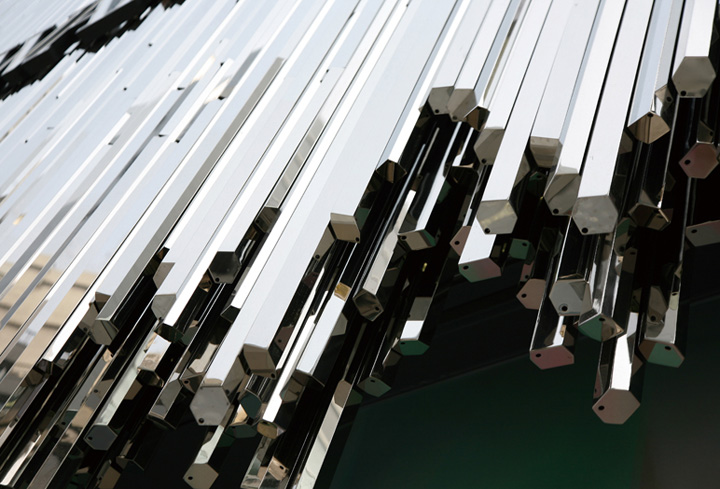

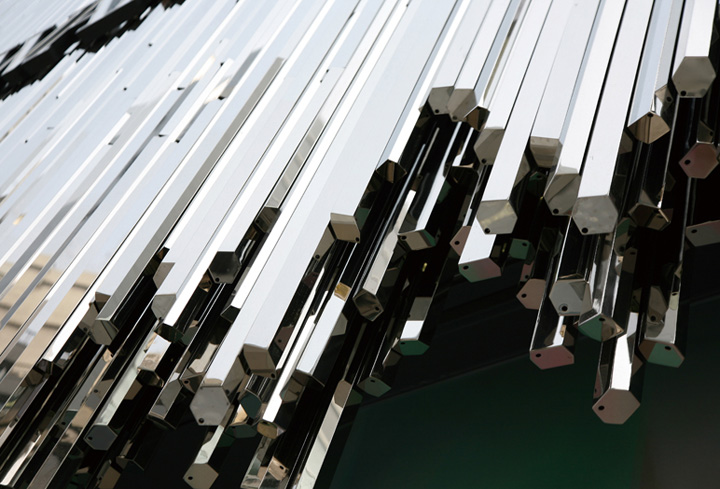

Opened in the spring of 2008, this 450-square metre, two-floored retail space is a rectilinear geode cavern – as if drained after submerged for millions of years in an overheated, mineral-rich Tokyo bay. Adorned with an array of simulations of stylised geological rock formations, concentric banding, typically found in geodes, is substituted with vertical patterning. Over 1500 hexagonal, stainless-steel rods form the grotto-like façade that frames the threshold to the main entrance. Once inside, mirrored quartz transforms into acrylic, milky quartz shards of interior wall panelling. There is, however, nothing mineral in either these appliqués or the exquisite lead crystal glass objets d’art on sale – as true crystalline structure is absent in glass. Swarovski crystal owes its spectacular specular reflection to the mixture of lead oxide and molten glass and the precision craftsperson that shapes its internal reflection.

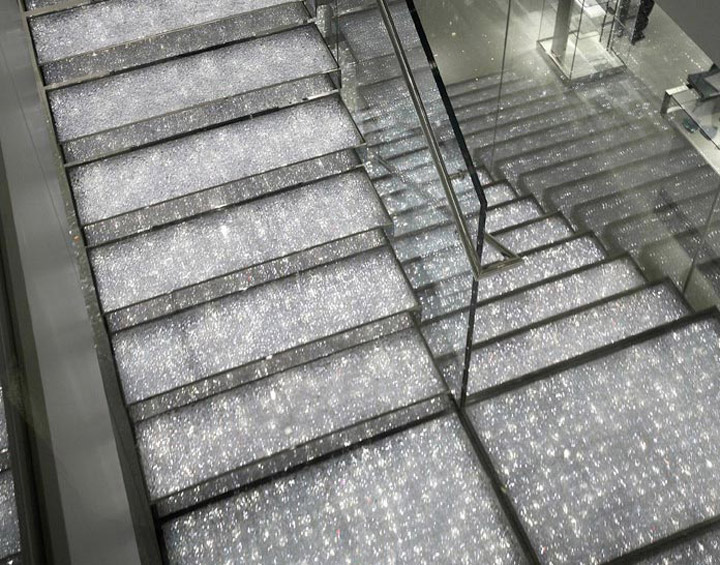

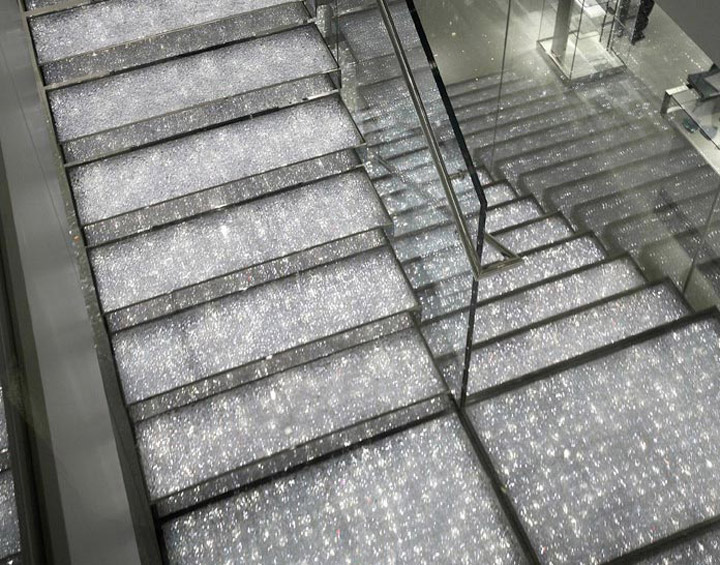

Between the embedded and freestanding display cases filled with jewellery, figurines, vases and bridal sets, one finds moments where Yoshioka places contemplative, mythical works. On the first floor a frozen shaft of falling irregular shaped crystals by Vincent Van Duysen puddles onto the floor. The second floor contains a smaller iteration of Yoshioka’s previous ceiling installation from his 2006 collaboration with Lexus L-finesse Evolving Fibre Technology in Milan. In this Shooting Star titled installation, however, the fibres that hang from the ceiling are shortened in an undulating pattern, suspending teardrop crystals – a similar installation (minus crystals) for his ‘Second Nature’ exhibition in late 2008. The staircase boasts cool LED radiant beds of crystal pebbles covered in glass treads. And suspended at the top of this glass enclosed stairwell is Tord Boontje’s chandelier Ice Branch, a hovering crystal encrusted mineral vein, as if extracted from a bed of sedimentary and volcanic rock.

As stated by Yoshioka’s office this is his Crystal Forest, a fairytale world where dreams and illusion mix to create a sensual aura of luxury. This is a strategy that has served him well, providing him with the necessary insight into his most recent project for Cartier: directing an exhibition of its illustrious collection. ‘Memories of Cartier Creations’ an exhibition in Tokyo’s Ueno Park in early 2009, materialises the true fairytale epics of the personalities that have owned and commissioned many of Cartier’s intricate works. Superimposing holographic narratives of photograph and movie reel archives against diamond and emerald embedded jewellery, memory becomes an effective medium over any contemporary quartz inspired installation.

Cartier takes the opportunity to commission Yoshioka to design two special objects located at the end of its exhibition. This necessity of embracing the innovation in contemporary design is a move that Swarovski Crystal Palace has aggressively understood for almost a decade – having not only previously commissioned Yoshioka and the 2005 chandelier Stardust, but also Marcel Wanders, Zaha Hadid and Tom Dixon to name a few.

Behind Yoshioka’s associations with these opulent labels, he has been carrying out design research in the growing of his own mineral crystals. Taking chair forms that are initially covered in a fur of polyester fibre (for facilitating crystallisation) whereby a water-soluble mineral materialises itself over time into a rough growth. These immersed forms, in vats of clear solution have recently been displayed in his ‘Second Nature’ exhibition.

It is here though that he illustrates his endeavour to move beyond the illusionary characteristics of the ‘concept’ of crystal to gain a material intelligence. The architectural theorist Sanford Kwinter referred to this when he said, “All matter, even totally disorganised matter, possesses some degree of active intelligence…” Transforming the chair into a crystalline artefact, its limited functionality is overlooked. What one is left to contemplate is its method of production and the extraordinary implications of cultivation. As Lawrence Hunter explains in Artificial Intelligence and Microbiology, “Crystals influence the matter around them to create structures similar to themselves…”

The notion that matter can be influenced to generate similar structures is compelling. Could these experiments be the first signs of new production techniques underwritten by Swarovski and Cartier?

http://www.australiandesignreview.com/projects/13000-Swarovski-Ginza

http://www.enlightermagazine.com/projects/swarovski-ginza-lighting-planners

Add to collection