“If you put art into design, people don’t throw it away,” declares British designer Ross Lovegrove, at the opening of his Convergence exhibition at the Centre Pompidou. ‘You wouldn’t throw away a Brancusi, so why would you throw away my bottle of water?’ Lovegrove is referring to his Ty Nant bottle (1999-2001), one of the first digitally-designed industrial products, in which he sought to capture the essence of liquid. Indeed, Lovegrove estimates that 60% of what he does is design, 40% is art, and all the while he is pushing technology to explore the parameters of liquidity and solidity.

“The show is called “Convergence” because it’s about science, physics, materials and evolution [in my work],” Lovegrove explains. Described as a “forward-looking retrospective”, it assembles a diversity of projects created over the last three decades. Count in furniture for Moroso, lighting for Barrisol and Artemide, plus futuristic pieces like the Ilabo Shoe for United Nude, which was 3D-printed using parametric software. What emerges is the singular independence of Lovegrove’s visionary thinking. “This is 10% of my production – everything I’ve done could fill the museum – but most of it is too commercial,” Lovegrove remarks.

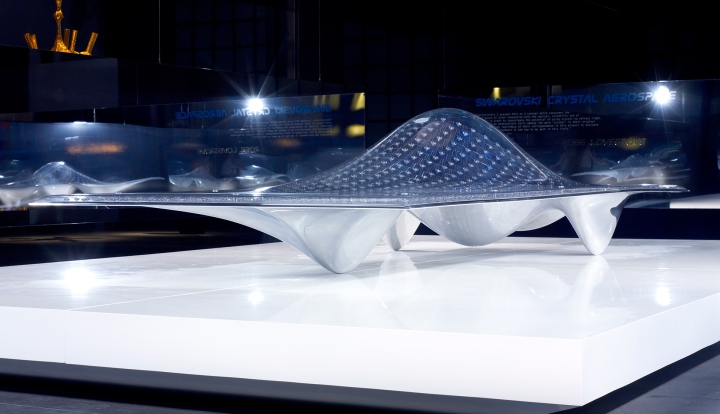

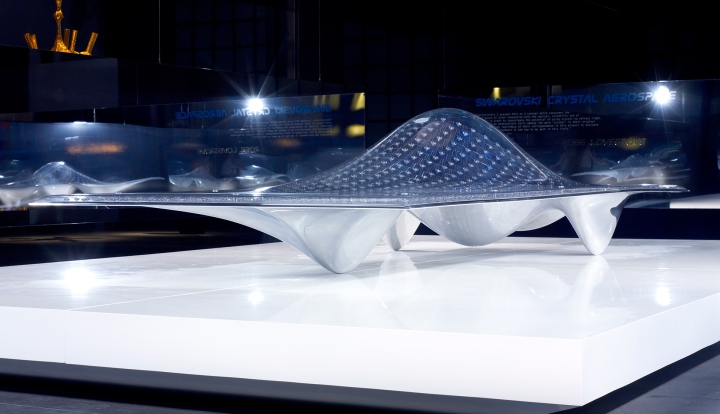

Greeting visitors at the entrance is Swarovski Crystal Aerospace (2005-2006), inspired by solar cars and created in collaboration with Sharp Solar Europe and Swarovski Optical Laboratories. “It’s a form that dematerialises in space and is emblematic of my creative, scientific work,” says Lovegrove, 58. “What if in the future we could grow products through cellular, 3D-bioprinting, not in a factory, and grow technology that would become more liquid and biological?” he asks. At the same time, Lovegrove’s advocacy of harnessing technology responsibly is a recurring concern.

“The car is the icon of our future – utopia or dystopia – and a method of seduction and pollution,” he asserts, whilst discussing his Concept-car Renault Twin Z (2012-2013). “The brief was that it had to be blue, so I found the guy in the south of France who had worked with Yves Klein on International Klein Blue. The best thing is the tyres, it’s a generative design that grows like a tree.” Challenging precedents has motivated Lovegrove since his student days.

Referring to Disc Camera (1982-1983), his MA project at the Royal College of Art in London that hugely reduced the weight of Kodak’s rotational film system, he enthuses, “When you’re creating a paradigm shift, there are no references – which is fantastic.” Lovegrove elaborates upon his ideas by filling his notebooks with drawings. Pictured in the header image of this article is the Pavillon Lasvit LiquidKristal (2012), made of undulating glass and designed using parametric tools: inside the structure are dozens of notebooks, displayed along with an African elephant’s skull dating from 1888.

“I have three of them; I collect incredible bones,” he says. “I have the original set of Henry Moore’s drawings [of the elephant’s skull]. I like big things, not small, microscopic things.” Looking ahead, what else would he like to do? “There’s a company in the US that makes replicas of dinosaurs’ skeletons that I’d like to visit,” he muses. “I love the rarity of the past, and because of that I can do super modern things.” Lovegrove will be using modern technology to push the boundaries of design on his own terms, however. “If I design something [in the future], I’m going to design for myself because I’m sick of brands.”

Design: Ross Lovegrove

http://www.frameweb.com/news/ross-lovegrove-exhibition-how-technology-is-transforming-design

Add to collection